“Between bridges and walls: The experience of an analyst in London”.

- Maria Pia Ciasullo

- Aug 25, 2024

- 7 min read

Circumstances of life made me emigrate to England, in July 2013; one feels the lack, one misses the customs, the family, everything is new, unknown, there is a relearning / a relearning. Somehow, it's more than just starting over...it's a rethinking or rethinking.

In my country 'I am someone' ... in my country I have a name and a surname, I have a history, experiences, trajectory, I don't need a business card. The streets, the neighbors, the smells, the customs; I am at home!

When emigrating, one feels that one loses the referents; those referents that gave us containment/stability. To reread Jung in another language, to hold a frame, to express what has been thought so many times, feels new and foreign.

Moving to London was a big challenge and despite the pain, the uprooting (and the implicit sacrifice), the frightening, the new, and the uncertainty, I had the hope of integrating into a society as “colorful” as it is colorful.

The German writer and poet Christian Morgenstern (1891), tells us; your home is not where you live, but a place where you are understood.

During all these years of profession, my colleagues, my symbolic family: SUPA had given me a frame of reference of work, protection and “acceptance”. And I had not questioned this internalization until I arrived in England, where my colleagues demanded very strict requirements when accepting this colleague from “distant” lands, of whom her name, her academic and professional trajectory, told them little. I then had to revalidate “my credentials” and make my way in an environment that, although not necessarily hostile, put up a wall of strict requirements for admission and professional recognition to cross.

Uprooting myself means leaving aside some paradigms and being open to the new and different. What clothes do I put on in front of my English colleagues?

“Being integrated and united is our deepest longing. Everything we do and accomplish, everything we desire and want, aims to achieve and attain above all one thing: to be accepted and recognized in a community to which we belong. Pride is the basic feeling we experience when we have accomplished something that secures us a place in the community of those to whom we want to belong.” B. Hellinger.

And in the longing to belong there is also the need to grow.

It may seem very foolish for someone at the age of 50 to consider such a drastic change of life and probably - as good Jungians - we attribute it to the mid-life crisis or, perhaps, without falling into arrogance, to a “call of the soul” or to the need to reinvent myself, to break “archetypes” or preformatted mandates in the social or personal imaginary.

In this regard, Jung tells us:

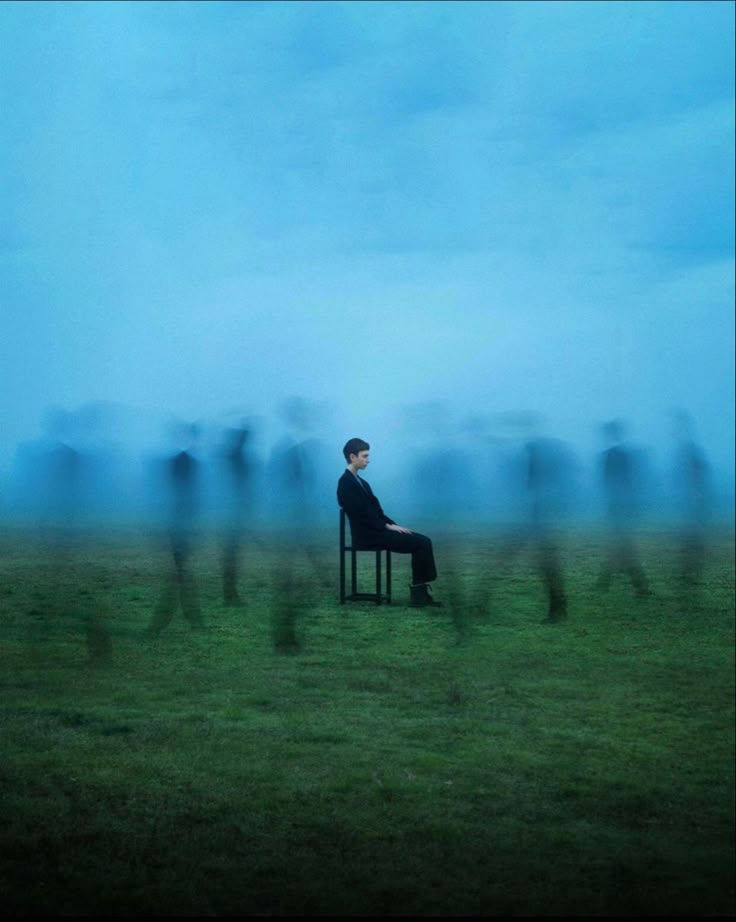

What is it, in the end, that induces a man to go his own way and emerge from unconscious identification with the masses as if he were emerging from an enveloping mist?

Not out of necessity, for there are many who have needs and take refuge in convention. Not because of moral issues, since nine times out of ten we also decide to resort to the conventional. What is it then that inexorably tips the balance in favor of the extra-ordinary? It is what is commonly called vocation; an irrational calling that leads man to differentiate himself from the herd and thus avoid the established paths.

Anyone who has a vocation hears the inner voice; like a call.

CW17 299f

In the book of Genesis, chapter 12, verse 1, the Lord tells Abraham, “Leave your country, your family and your father's house, for the land that I will show you”. Leaving behind your country, your family and your roots, means undressing from that Person who accompanied us for so long and with whom we felt in our skin or in a familiar comfort zone. We are left, necessarily, naked and vulnerable ... stripped of certainties, facing a new challenge that is “imposed” on us from individuation.

Losing external referents; learning to deal with other codes, feeling foreign, not having tangible contact with friends, family and colleagues; we are left, apparently, without a place ..., or at least with the need to create or forge a new identity for ourselves. But we are tied to a place, whether consciously or unconsciously. We need to know where we “locate” ourselves in relation to feelings, ideas, links, memories that we have and that hold us, a place both in the external and internal world. When we are out of place, we need to put things “in their place”.

As Gustavo Barcellos says: “We belong to a place, a hometown, a neighborhood, a house or a sea. Belonging belongs to the archetypal constellation of shelter. There is also the womb, the mother, the homeland and the tomb”.

We try to build bridges; bridges that cross borders. And at times we come face to face with walls which, as Barcellos says, are borders taken to their pathological extreme. We need to enter into the idea of frontier to understand the psyche of our patients.

Borders speak, walls leave us mute.

“There are borders everywhere; borders of race, of age, of health (between illness and cure), between reason and madness and also psychological borders between Ego and soul, between Ego and the Other, between Ego and Unconscious. They evoke archetypal fantasies of territoriality and domination, sovereignty and independence, equality and difference, local or foreign.”

Drexler; Frontiers.

WORKING WITH OTHER CULTURES

How open are we to integrating foreign cultures? Different attitudes towards gender, sexuality, religion, values, individualities and collectives.

We have been trained with established cultural patterns for working as analysts, therapists or supervisors, in Murray Stein's words “the 10 commandments”. H. Abramovitch speaks of a Jungian super-ego, an internalized collective voice of what a Jungian analysis should be like. As William James rightly said: “A great many people think they are thinking when they are merely rearranging their prejudices”.

But when working with other cultures, we have to relativize our beliefs and convictions or at least rethink them.

FROM TRADITION TO INNOVATION (Crowther and Jan Wiener)

Archetypal images unite us, bind us, but each of these archetypal patterns find in each culture, a way to express themselves. As a human species, we all share a common psychological heritage. It is in this sense that we can offer psychotherapeutic help to people from different cultures, building bridges between cultural diversity.

The Spanish analyst Ricardo Carretero also refers to bridges and says: “Psychotherapy is stipulated on the bridge of meaning that is established between the psyche of the therapist and the psyche of the patient. On the construction of this dialogic bridge, then, will depend on that interaction between psyches which, after understanding the nature of the affliction in the patient's psyche, will then allow it to be directed towards a path of health”.

In the first phase, the patient is on the edge of confession (hopelessness, grief, pain, the sufferer; passive position). He wants to communicate the nature of his pain and to make himself understood. The therapist is on the shore of welcoming this confession, waiting for the right condition to be established for the construction of the bridge of meaning. In this phase the patient connects with hope (of his patient being, of the one who hopes), glimpsing the future.

The cure comes from the construction of this bridge of meaning where both psyches are transformed. We must be humble and go beyond our cultural assumptions ... and trust that the Self is always doing its work.

EXPLORING CULTURAL COMPLEXES AND IDENTITIES

The British analyst Jules Cashford, speaks of a cultural unconscious or a cultural level of the psyche that exists between the personal and collective unconscious. Thus, we can also speak of cultural complexes (as well as individual ones) and refer to the psychopathology of a group or nation. Thomas Singer refers to cultural complexes as “a set of emotionally charged ideas and images that tend to cluster around an archetypal core and are shared by individuals within a defined collective”.

For Anne Shearer, cultural complexes are based on repeated historical experiences that are rooted in the cultural unconscious of a group. They generally have to do with traumatic experiences, discrimination, feelings of oppression and inferiority.

C.C. are an expression of the need to belong, they provide cohesion and a sense of group and kinship.

We are influenced by the cultural complexes of the place where we live and probably, the less discriminated our personal complexes are, the more we are influenced by the cultural ones.

MOTHER TONGUE OR ANOTHER LANGUAGE?

The mother tongue refers to early childhood, emotional development and symbolization processes. The use of another language in psychotherapy may be used as a defense, since it was learned at a later stage of development. It is the language that generates the least distress. Early experiences may be overlapped with defenses.

But true listening has no “language”. Listening from the heart is more important than language translation. Speaking in another language involves a double interpretation, interpreting the language (with its cultural differences, sense of humor, gestures) and interpreting the speech per se. “Speaking the same language” has other implications, and does not involve speaking the mother tongue.

But there is the underlying fantasy; “if you speak another language, then you think, feel and perceive differently”.

When we speak another language, we lose the nuances, the subtleties, the lapses and the humor.

As for typology, is there a rotation of functions when we speak another language? The lower function is unconscious. When we speak another language, we need to find the “unknown” word (unconscious) and perhaps we resort to the lower function to do so.

The Russian analyst and interpreter Kama Melik, in her article “Bridging two realities” argues that when we introduce another language (which is not our mother tongue) a triangulation (analyst-analyzing-language) occurs.

The Hermes (in his Trickster phase) is constellated, subtly altering the meaning of what he interprets, in tonality, commentary and irony.

The foreign language acts as a border, a container, a pillar that supports the neutral space, a womb that holds what is not yet ready to emerge. It bridges the gap between conscious - conscious and marks a border at the unconscious level.

But the yearning to be understood crosses the gap that, instead of separating two consciousnesses, unites them. The effort we make to transmit meaning in another language allows a “bridge of understanding” to be built. The transcendent function is put into play, without the use of words.

As my friend and colleague Guislaine Morland says, “writing and thinking in another language frees us from those other roles you have in your mother tongue. And speaking more than one language gives a person the freedom to go against the rules of a collective identity”.

But without a doubt, I am more present speaking my own language.

BACK HOME

Robert Frost (1914), transcribes a dialogue between a farmer and his wife:

“It all depends on what you mean when you say home;

Your home is a place where, when you arrive, they have to let you in.

And she replies: your home is something that somehow belongs to you without having to deserve it.”

And this is exactly what I felt when I came home; I was let in ...

María Pía Ciasullo has a degree in Psychology, UDELAR (Universidad de la República Oriental del Uruguay).

Postgraduate and Master in Psychotherapy with orientation in Jungian Analytical Psychology, Catholic University of Uruguay.

Jungian Analyst, Senior Member IAAP (International Association for Analytical Psychology). Zurich.

Uruguayan Certificate of Psychotherapy (Uruguayan Federation of Psychotherapy - FUPSI).

President of the IX Latin American Congress of Jungian Psychology. Montevideo, October 2023

Founding member of SUPA (Uruguayan Society of Analytical Psychology).

Founding member of FUPSI (Uruguayan Federation of Psychotherapy).

Member of GAP (Guild of Analytical Psychologists) and IGAP (Independent Group of Analytical Psychologists), accredited by UKCP (UK Council for Psychotherapy).

Secretary for Uruguay for SUAPA (Uruguayan-Argentinean Society of Analytical Psychology).

Analyst and supervisor in the training of…